When people hear the word “pearl,” they often picture a perfectly round, luminous gem—something elegant and classic.

But what about “Akoya”?

As someone who specializes in Akoya pearls, the word instantly brings pearls to mind for me.

However, even among Japanese people, those who aren’t particularly interested in pearls may not immediately associate “Akoya” with pearls.

Several years ago, at a jewelry show in Hong Kong, I met the owner of a jewelry brand who had never heard the word “Akoya.”

She pointed to a tray of Akoya blue baroque pearls at our booth and asked, “What are these?”

When I replied, “Akoya pearls,” she gave me a puzzled look and repeated, “Akoya?”

I repeated, “Yes, Akoya pearls,” and she tilted her head.

Then she said, “Don’t you mean Mikimoto?”

After a brief back-and-forth, like trying to tune an old radio to the right frequency, we finally reached an understanding.

She explained, “In my country, Italy, nobody knows the word ‘Akoya.’ What you’re calling Akoya pearls—we call them Mikimoto pearls.”

I laughed and replied, “I see! ‘Mikimoto’ is probably easier to understand.”

What puzzled me was that her company’s catalog was quite impressive.

The pieces featured dazzling and elegant jewelry findings, many adorned with diamonds.

Among them were also pieces using Akoya pearls—clearly displayed in the photos.

And yet, the owner of the brand didn’t know the term “Akoya.”

According to her, in Italy, the name “Mikimoto” is more commonly recognized than “Akoya.”

And honestly, I told her, I agreed—“Mikimoto” might indeed be easier to understand.

However, the issue is that people might end up calling any Akoya pearl “Mikimoto,” even if it has nothing to do with the company.

That would be quite a mix-up.

Years later, I sold Akoya pearls to another Italian customer through Etsy.

This time, she knew exactly what “Akoya” meant.

Of course, two people don’t speak for all of Italy.

But it’s true that now and then, I meet someone who asks, “Akoya? What’s that? Is it a real pearl?”

So today’s topic is: “Is Akoya Pearl a Real Pearl?”

If pearl farmers in Japan heard this question, I imagine many of them would be furious.

But let’s take a look at the history of Akoya pearls.

The Ancient Origins of Pearls in Japan

Japan’s oldest historical record is a book called the Nihon Shoki, completed around the year 720.

In it, there is a passage stating that sometime between 29 BCE and 70 CE, during the reign of Emperor Suinin, white pearls (shiratama) were offered as tribute from the province of Shima.

Although Emperor Suinin is considered a legendary figure, and his historical existence has not been confirmed, the fact that the Nihon Shoki was compiled in 720 allows us to confidently say that pearls were already valued as prestigious tribute items in Japan at that time.

Incidentally, the ancient province of Shima corresponds to today’s Ise-Shima region in Mie Prefecture—home to none other than Mikimoto himself.

So while the pearls were highly prized as early as the first century, they weren’t referred to as “Akoya” at the time.

Until the late 1800s, they were simply called “pearls” or “white pearls.”

When “Akoya” Became “Akoya”

The Edo period (when samurai roamed the land) came to an end in 1868, and Japan entered the Meiji era.

This marked a time of rapid modernization and a surge in scientific research, including pearl cultivation.

It was during this time that the pearl-producing mollusk Pinctada fucata martensii was identified as being particularly suitable for cultured pearl production.

As biological classification advanced, the name “Akoya-gai” (Akoya oyster) was scientifically and commercially adopted.

Personally, it’s fascinating to imagine that while samurai were giving up their swords and embracing Western culture, research into pearl oysters and pearl cultivation was also quietly progressing in the background.

A Personal Side Note on the Meiji Restoration

This may be off-topic, but I believe the transition from the Edo to the Meiji era was effectively a large-scale coup d’état.

Many highly capable samurai of low status rose up and gave their lives for what they believed in.

At the time, these “opening-the-country” samurai worked across Japan with the shared belief that even if they died, others would carry on their ideals.

In modern terms, they were trying to overthrow the Japanese government.

While the Meiji leaders who came afterward appear impressive in hindsight, I believe the original samurai had far greater skill and experience—almost like comparing adults to children. (That’s just my personal opinion.)

Today, self-sacrifice for ideals is often seen as dangerous thinking.

But I believe the spirit of “protecting something greater than yourself” still exists—especially in parents, who instinctively value their children’s lives more than their own.

…Well, that’s enough of a detour. Back to pearls.

The Rise of Cultured Akoya Pearls

In the late 1800s, as Japan modernized during the Meiji era, a growing number of people saw the potential for huge profits if pearls could be cultivated artificially.

They began experimenting with Akoya pearl farming.

Strictly speaking, it wasn’t Kokichi Mikimoto who first succeeded in producing perfectly round cultured pearls.

It was a man named Tōkichi Nishikawa.

Once Mikimoto caught wind of Nishikawa’s breakthrough, he arranged for his daughter to marry him—securing Nishikawa’s techniques and success under the Mikimoto name.

This is well-known in the pearl industry.

However, because Mikimoto had already established a reputation and brand, few people objected.

Besides, there was no real benefit to criticizing a giant like Mikimoto Pearls—only risk.

As for me, I’m free to write things like this on Flower Jem’s blog because I’m fairly confident that few pearl dealers will ever stumble upon these articles.

Patents, Legal Battles, and a Monument of Defiance

In 1905, Mikimoto succeeded in producing round cultured pearls.

By 1908, he had obtained a patent.

But he wasn’t the only one interested in pearl farming.

Many local pearl farmers and fishing communities were also pursuing the same dream.

With Mikimoto’s patent, these independent producers were suddenly blocked from cultivating pearls—even from working in the ocean.

Three lawsuits followed.

Eventually, the court ruled that “pearl cultivation should be a freedom available to everyone.”

A monument commemorating this legal victory still stands in Ise today.

In essence, it reads: “We beat Mikimoto! Now we can cultivate pearls freely—hooray!”

This monument isn’t far from Mikimoto’s own base of operations.

But hardly anyone pays attention to it.

After all, nearly 100% of tourists visiting Ise are Mikimoto fans.

Akoya Pearls Go Global—And Cause Trouble

In 1919, cultured round Akoya pearls were introduced to the London market by Mikimoto at 25% lower prices than natural pearls from the Persian Gulf or South Seas.

European jewelers were not pleased.

Two years later, in 1921, in the city of Kobe, a man named Yasue Tōdō succeeded in developing a technique for stain removal and toning (adjusting the color) of pearls.

This groundbreaking method attracted pearl dealers from all over Japan.

Thanks to Kobe’s status as the largest port city in western Japan, pearls processed there quickly made their way across the globe.

It was around this time that Kobe became known as “The Pearl City.”

By 2025, sadly, less than 30% of Kobe residents even know this.

A Global Turning Point: The Paris Trial

In 1924, a pivotal legal case took place in Paris—a trial to determine whether cultured pearls and natural pearls were fundamentally different.

The court ruled that there was no essential difference between the two.

This decision marked a turning point: cultured pearls were officially recognized as legitimate gemstones around the world.

Looking at this now, I can’t help but think—perhaps it really was Mikimoto who made it all happen.

He was known to be a bold gambler, a man of extremes.

Strong-willed, fiercely competitive.

If he had been a timid person, perhaps he would have quietly stayed in Japan and cultivated pearls only for the domestic market.

But Mikimoto wasn’t that kind of man.

He charged into the world, went to court, and won.

I’ve spoken with several elderly people connected directly or indirectly to Mikimoto’s pearl farms, and they all say the same thing: he was absolutely crazy—in both good and bad ways.

The Collapse of the Natural Pearl Industry

Among all the stories in pearl history, this one strikes me as particularly fascinating:

In 1932, the global spread of cultured pearls—far cheaper than natural ones—caused a major disruption.

Nations like Bahrain and Kuwait, whose national incomes relied on natural pearls—up to 90%—suddenly found their economies in crisis.

In response, they shifted their focus to oil.

Yes, you read that right: the oil-rich nations we now know were once pearl nations, until the appearance of Akoya pearls changed their course forever.

Cultured pearls created oil kings.

Meanwhile, Japan…

Well, let’s just say our path turned out a little differently.

The Rise of Freshwater Pearls

Three years later, in 1935, the cultivation of freshwater pearls using Hyriopsis schlegelii (a freshwater mussel) began in Japan.

By 1938, Japan’s domestic pearl production reached approximately 6 tons.

But in 1940, with the onset of World War II, luxury items like pearls were banned under government order.

It makes sense—pearls don’t win wars.

Post-War Restrictions and Revival

In 1945, following Japan’s defeat in World War II, the Allied Occupation Forces (GHQ) limited pearl trading to just five authorized companies.

The company I once worked for was one of those five.

In 1949, the restrictions were lifted, and the Japanese pearl industry began its slow recovery.

The Peak of the Akoya Era

From that point forward, the Akoya pearl industry soared.

Major pearl companies opened branches in New York and Zurich.

In 1966, Japan’s domestic pearl production reached its postwar peak: 150 tons.

I can only imagine how polluted the oceans must have been by then.

At the 1970 Osaka World Expo, there was even a “Silk and Pearls Exhibition.”

Back then, both silk and pearls were among Japan’s top export goods—something that’s hard to imagine today.

But by 1974, production had fallen to 37 tons—a quarter of its peak.

Overcrowding of oyster baskets had gone too far.

The vast number of Akoya oysters hanging in the sea consumed all available nutrients, and their waste accumulated on the seabed in thick, suffocating sludge.

People say Japanese are polite, but in this case, I think we lacked restraint.

Even now, fish like sanma (Pacific saury) and squid are disappearing from Japan’s coastal waters.

After listening to people in fisheries, government agencies, and logistics companies, the general consensus is: overfishing.

Shrinking Waters, Dying Shells

From this point onward, the Akoya industry began to shrink.

In 1992, red tide caused mass deaths of Akoya oysters across Japan.

The company I worked for had five pearl farms, and at one of them, every oyster died.

To survive, the farm’s manager ordered the staff to cut down and sell trees from the mountain the company owned.

“I had to do whatever it took to stay alive,” said a 72-year-old veteran staff member who told me the story, smiling.

The same kind of mass mortality happened again in 1996.

By then, the oysters had undergone over 20 generations of inbreeding, creating genetic weakness—a problem we still face today.

By 1999, Japan’s pearl production had fallen to just 25 tons.

Once an Akoya oyster dies, restarting the farm is incredibly difficult.

Even after inserting a nucleus into the oyster, it takes at least a year before any pearl can be harvested.

No income during that time.

And if after waiting all that time, the pearl turns out poor in quality… it’s game over.

Decline, Tragedy, and a Sudden Surge

In 2011, production fell even further, to just 15 tons.

In 2019, another massive die-off occurred.

Coincidentally, this happened just as COVID-19 began to spread.

Then, in 2023, after the pandemic began to ease, Akoya pearl prices soared to their highest levels in over a century.

Production was down, economies were rebounding, and explosive buying power from China all collided in a perfect storm.

Japanese consumers, however, were left behind by this sudden rise.

A Personal Memory—The Disappearing Akoya Oyster

If you’ve read this far, you might agree: Akoya pearls carry a long, undeniable history.

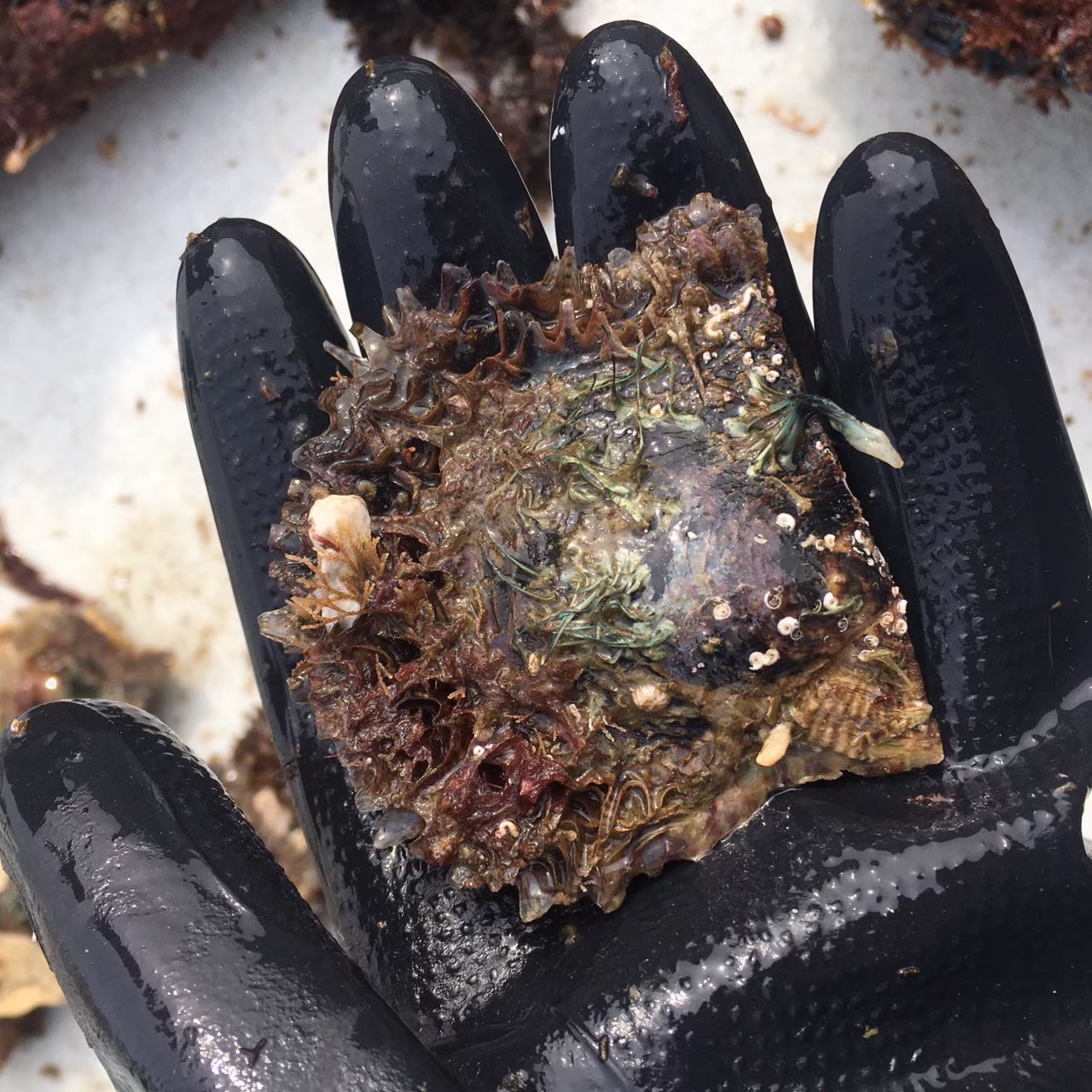

There was a time, just 20 years ago, when wild Akoya oysters were so abundant that in certain areas, you could find as many as you needed clinging to mooring ropes and seawalls.

Back then, it was common to harvest three million wild oysters per year.

When I first joined the pearl industry, I took part in one of those annual oyster gathering trips.

I was excited to see it firsthand.

We collected… only one hundred.

Had the oysters all migrated north due to warming seas?

Or had they simply died out?

No one could say for sure.

Small, Humble, and Beautiful—The Japanese Way

Compared to black-lipped or white-lipped oysters, Akoya oysters are tiny.

Just like how Japanese people are often smaller than Westerners.

And while their pearls may be modest in size, Akoya pearls are said to have a finer, more delicate nacre than the bold, fast-growing pearls of warmer waters.

I’ve heard people say Japanese skin is more beautiful than Western skin…

Honestly, I’ve never been convinced of that myself, so I’ll refrain from making any claims.

That said, I’ve often been told by overseas customers:

“8 millimeters? That’s too small. Don’t you have anything 15 millimeters or bigger?”

Well, in the world of Akoya, 8mm is considered large.

Just like how a Japanese person who’s 180 cm tall is unusually tall.

This “almost too small” feeling—this subtle lack—is exactly what I find so beautiful about Akoya.

It’s distinctly Japanese.

Though Akoya oysters can be found in places like Vietnam, they’re mainly native to Japan.

They’re small, humble, and quietly luminous.

Please continue to keep watch over these fragile yet brilliant little creatures.

In Closing

If you’re visiting Flower Jem’s website, you likely already know about Akoya pearls.

But if you’ve ever wondered, “What does Akoya actually mean?”—I hope this article helps.

Better yet, go ahead and Google it.

And after reading this brief overview of Akoya’s history, I think you’ll agree—

this isn’t just a name.

It’s a legacy.

In a way, Akoya pearls have walked alongside Japan’s postwar rise and its decline.

Comment