From yesterday to today, I made a video about how to make an All-knot necklace.

There have been several videos in the past that recorded the All-knot production process, but in those videos, there were comments that my hands were in the way or that it was difficult to understand. The reason for recording those videos was to have people check the quality of the pearls, to let them know that I actually make them, and to let them know roughly how All-knot is made. However, there are many videos on YouTube that are quite well-made. Among them, 99% of my videos are unedited and just run-through videos. I don’t have the ability to edit videos, and I don’t want to spend much time editing videos. However, I felt the need to prepare at least one relatively detailed video about All-knot, so I made one this time. It took quite a long time, more than 8 hours. I spent 18,000 characters on the subtitles, but when I made them, they only took about 15 minutes. Also, the one-hour video was quite large at 25G. Since one photo is 8M in size, it is a huge capacity. So it took more than an hour just to save the edited video to my computer. It was a lot of work. This time, the subtitles I made for the video were 18,000 characters long, so I decided to leave them here. In order to make this video, I turned down a friend’s invitation to a barbecue. It’s a shame, but my friend has barbecues quite often, so I plan to join him soon. So, I’ll leave the subtitles below.

**************************************************

This video shows the complete process of creating a necklace using the All-knot technique.

The method itself is quite simple, so if you’re interested in mastering All-knot, this video will serve as a helpful guide.

I’ve been making necklaces using All-knot for five years, but I’m sure you’ll be able to do it even better.

There are a few tips to avoid mistakes when doing All-knot.

First, always ensure the thread remains untwisted.

I often find myself struggling with tangled threads, and this is usually the cause.

I tend to rush and ignore slight twists in the thread, which is not a good practice.

It’s important to fix any twist as soon as it appears.

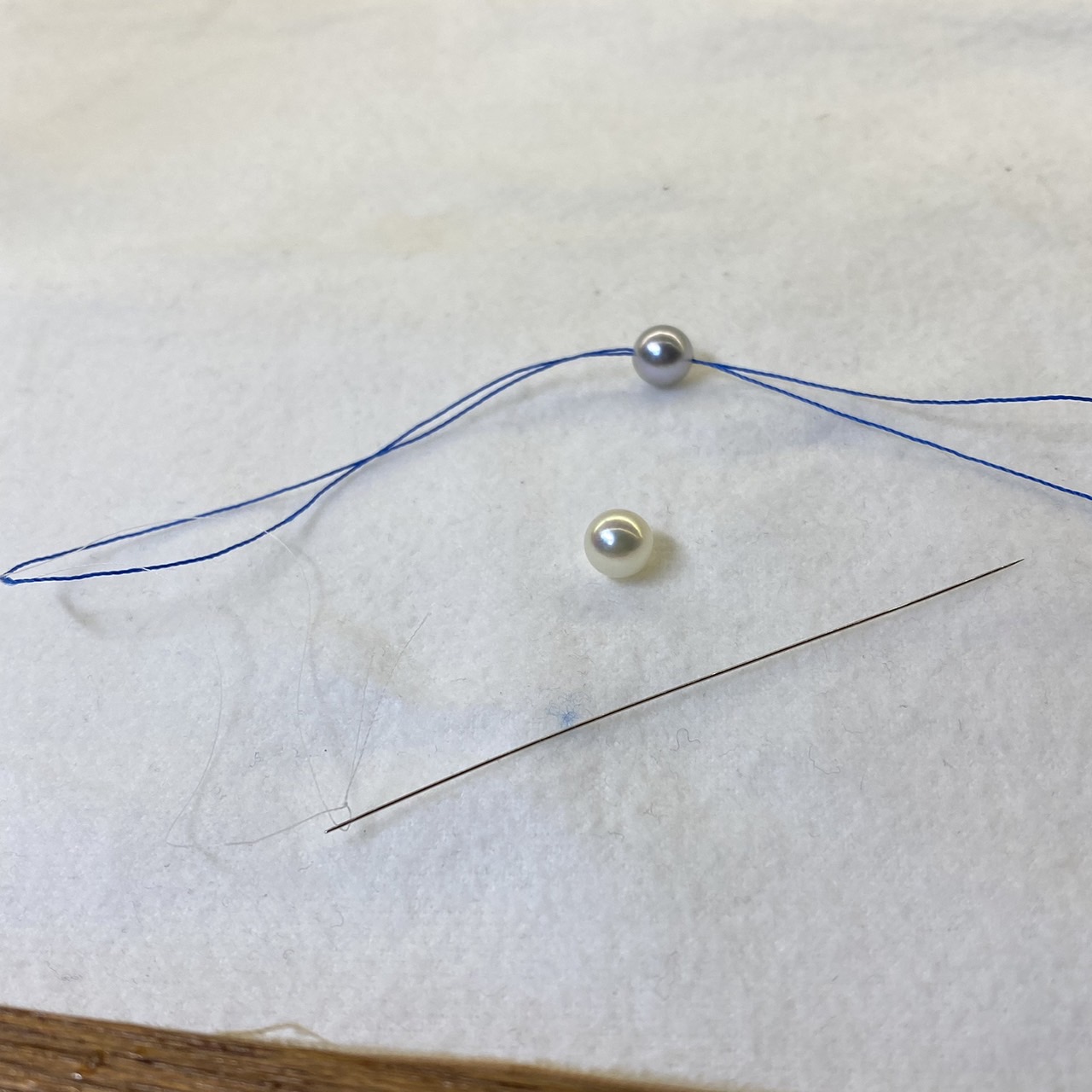

Also, the size of the thread and the size of the pearl’s hole are crucial.

In my case, I use thread sizes #20 or #30.

These sizes, from #20 to #30, are considered relatively thick.

Most craft stores don’t sell them, but luckily, I live in Kobe, Japan, a city known for pearls.

There are pearl supply stores here where I can purchase the appropriate thread.

The size of the pearl holes is 0.7mm.

Another very important point is that the holes of the last three pearls in the All-knot process must be at least 0.8mm or larger.

For any type of necklace, the thread used is made up of two strands.

In All-knot, these two strands pass through each pearl twice, meaning each pearl ends up with four strands of thread passing through it.

For the last three pearls, six strands of thread will pass through.

You can see this towards the end of the video, which explains why there are six strands.

Therefore, the holes of the last three pearls need to be larger.

If not, the thread won’t pass through at the very end, ruining all your hard work.

I’ve broken about eight needles at this stage and asked a pearl supplier for advice, only to be told,

“Did you make sure the last three pearls had larger holes?”

Another key aspect of the All-knot technique is to tie each knot carefully.

As mentioned earlier, the thread passing through the necklace is two strands as one.

Even if it looks like you’ve tied a solid knot, sometimes one of the strands might be loose.

If one strand is loose, the knot can look bigger, and after finishing the All-knot necklace, the knot next to some pearls might loosen, causing the pearl to move.

It’s important to check that each knot is properly tied during the process.

Also, each time you tie a knot, make sure the pearl is snug against the knot to confirm a good fit.

It’s hard to explain with words, but after you tie a knot, instead of immediately moving to the next pearl, try seating the pearl on the knot.

If something feels off, it may indicate that the knot wasn’t tied well.

Always check to ensure the knot and pearl sit together comfortably.

If the knot wasn’t tied properly, you’ll notice the pearl doesn’t sit well, and you’ll sense something is wrong.

The person who taught me All-knot told me this is an important habit to develop.

These are the key points for All-knot.

Now for my personal opinion.

The purpose of my All-knot necklace creation is to highlight the colored thread.

For this reason, the knots need to be larger.

Normally, in All-knot, each knot is tied once.

However, in my case, I tie two knots between each pearl.

I create two knots each time.

Additionally, depending on the situation, for each “knot,” I pass the thread through the loop twice to make the knot larger.

You might be thinking, “What?”

By definition, a “knot” is when you pass the thread through the loop created by the thread itself.

“Passing it through twice” means I thread the string through the loop twice.

This way, the knot becomes larger.

Depending on the nature of the thread, if you tie two knots, the space between the pearls will be wider.

On the other hand, if you pass the thread through the loop twice for one knot, the knot itself becomes bigger, but the space between the pearls will be narrower than with two knots.

The size of the knot between pearls is a matter of personal preference, so I encourage you to experiment and find your own preference.

It’s a very challenging process, but also a fascinating one.

Here is the English translation of your text:

How to Make Two Knots Where the Thread Passes Through the Loop Once:

You can create several variations, such as making two knots where the thread passes through the loop formed by the thread once, making three knots where the thread passes through the loop once, or making two knots where the thread passes through the loop twice.

The method can be adjusted depending on the type of thread or the size of the pearl holes.

This not only affects the spacing between the pearls but also the overall tension of the necklace.

It can result in a necklace that is flexible and sways gently, or one that is semi-rigid with the strength of a wire, depending on how you create it.

By the way, the thickness of the needle I use is 0.43mm, which I purchased from a craft store.

The thinner the needle, the easier the work becomes.

Also, when making the necklace as shown in the video, it’s necessary to hook one end of the necklace onto something.

People in the pearl industry often recommend using a doorknob, but I have a hook on a shelf where I hang the necklace.

There are several key points to making a necklace with the All-knot technique, but I personally think the most important one is to prevent the thread from getting tangled.

Since I’m quite clumsy, I find myself constantly battling with tangled threads.

However, in all the All-knot tutorials I’ve watched on YouTube, no one ever seemed to have tangled threads.

Now, this is all I have to share about the All-knot technique.

Although I’ve written about this many times before, let me explain why I’m so passionate about All-knot.

About 10 years ago, I started working at a pearl company.

I joined in August, and by the end of November, I was sent on a business trip to an Akoya pearl farm.

This was because pearl harvesting begins at the end of November each year.

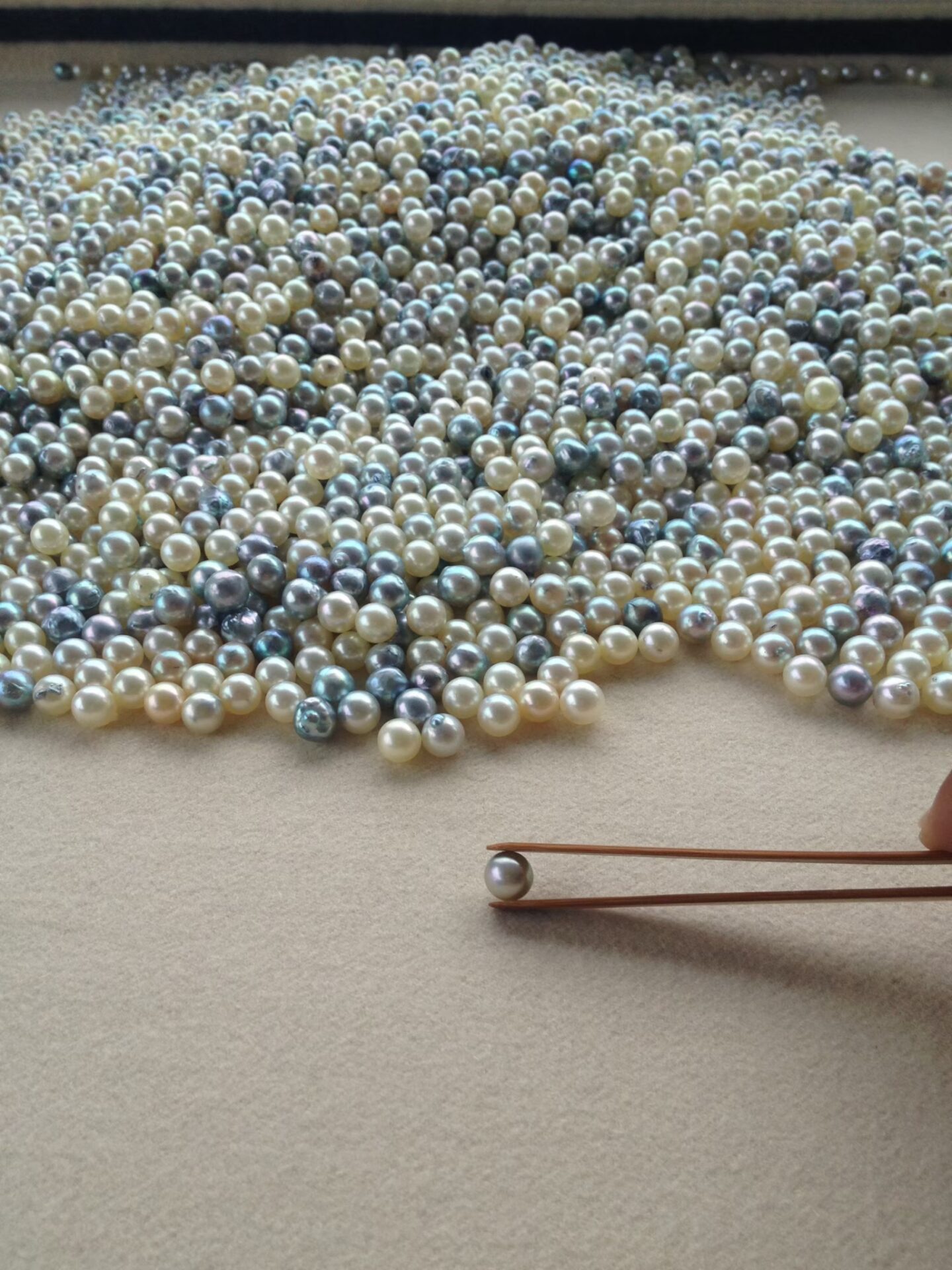

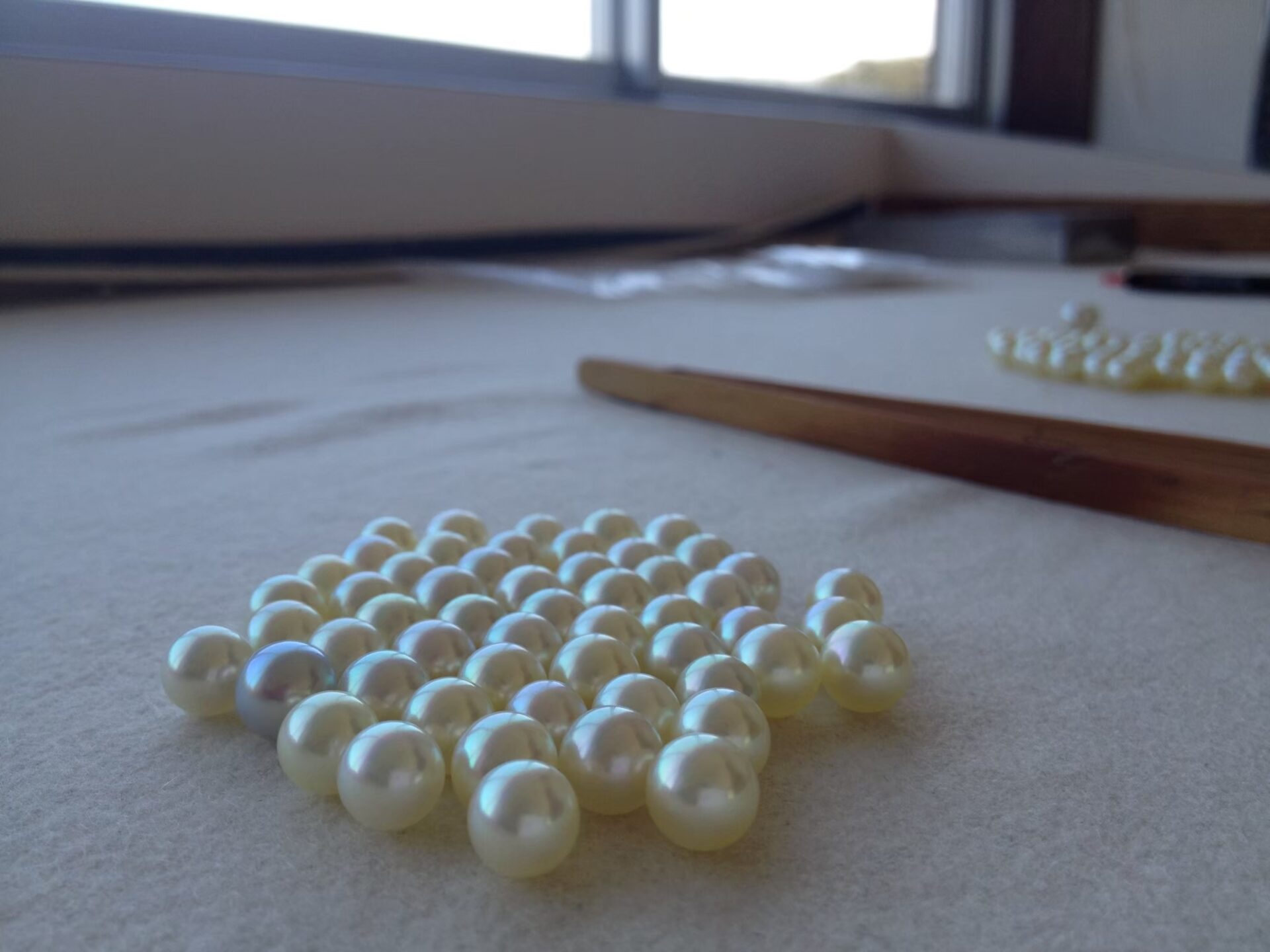

At the farm, we would sort the Akoya pearls that were harvested daily.

Only a limited number of people were allowed to sort the pearls: the farm manager, a few executives, and myself and my boss from the head office.

The rest of the workers were busy with tasks like harvesting the pearls from the sea, retrieving Akoya oysters, gathering the oysters at the worksite, and extracting the pearls.

My boss explained that only executives were involved in the sorting process to prevent theft, but I also felt it was because of the shortage of manpower.

Around 22 kilograms of pearls are harvested each day.

If all of these pearls were 7mm in size, that would be roughly 150,000 pearls.

I traveled back and forth between two pearl farms with my boss, sorting pearls from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day.

We worked without a single day off from the end of November until Christmas, and then resumed sorting on January 4th until mid-February, again without any holidays.

The pearl harvest is aligned with the timing of pearl auctions.

The first auction, held in mid-January, features only top-grade pearls that are round, flawless, and have a strong luster, called Hama-age-dama (freshly harvested pearls).

Famous pearl companies like M and T also participate in this auction.

Following the top-grade auction, there is an auction for slightly lower-ranked pearls, and then, in early February, an auction for second-grade Hama-age-dama pearls (which are round with minor blemishes and decent luster).

Each auction lasts about 3 to 5 days.

In March, an auction is held for mid- to low-grade pearls, which tend to be the most abundant.

This auction typically lasts for about a week.

During the auction period, the pearl association would contact me each time bids were placed.

There are over 300 lots of pearls up for auction, each with an estimated value determined internally.

Only when the bid falls below this estimate do we review it internally, but over 95% of the lots receive bids that exceed the estimate.

While sorting pearls daily, I also had to keep track of the auction updates provided by the pearl association, compiling the information by the end of each day.

For the first three years after joining the company, the harvest season was incredibly busy.

I would spend my days sorting and often work on paperwork until 4 a.m.

There are millions of Akoya oysters being cultivated for pearls.

For each batch of pearls harvested, we needed to calculate when the nuclei were implanted, the number of oysters harvested, and the yield of pearls extracted from those oysters.

After about two weeks of sorting, the pearls are divided into lots, which are carefully weighed in the presence of executives.

I was responsible for compiling the weighing data into tables, which was an incredibly tedious task.

Even though the pearl lots are weighed within the company, they are reweighed by the Pearl Association when they are submitted for auction, which often results in discrepancies. Each time this happened, I had to adjust the information accordingly.

Although the paperwork was challenging, the pearl sorting was even more difficult. It took me three harvest seasons to gain a basic understanding of sorting, which means it took about three years to learn.

In my first year, my boss instructed me to “remove the pearls with thin nacre from this lot,” out of a selection of about 300 pearls, but to me, all the pearls looked the same.

Even a beginner can easily tell the difference between pearls with and without wounds or varying levels of luster. However, distinguishing between thick and thin nacre was extremely difficult for me.

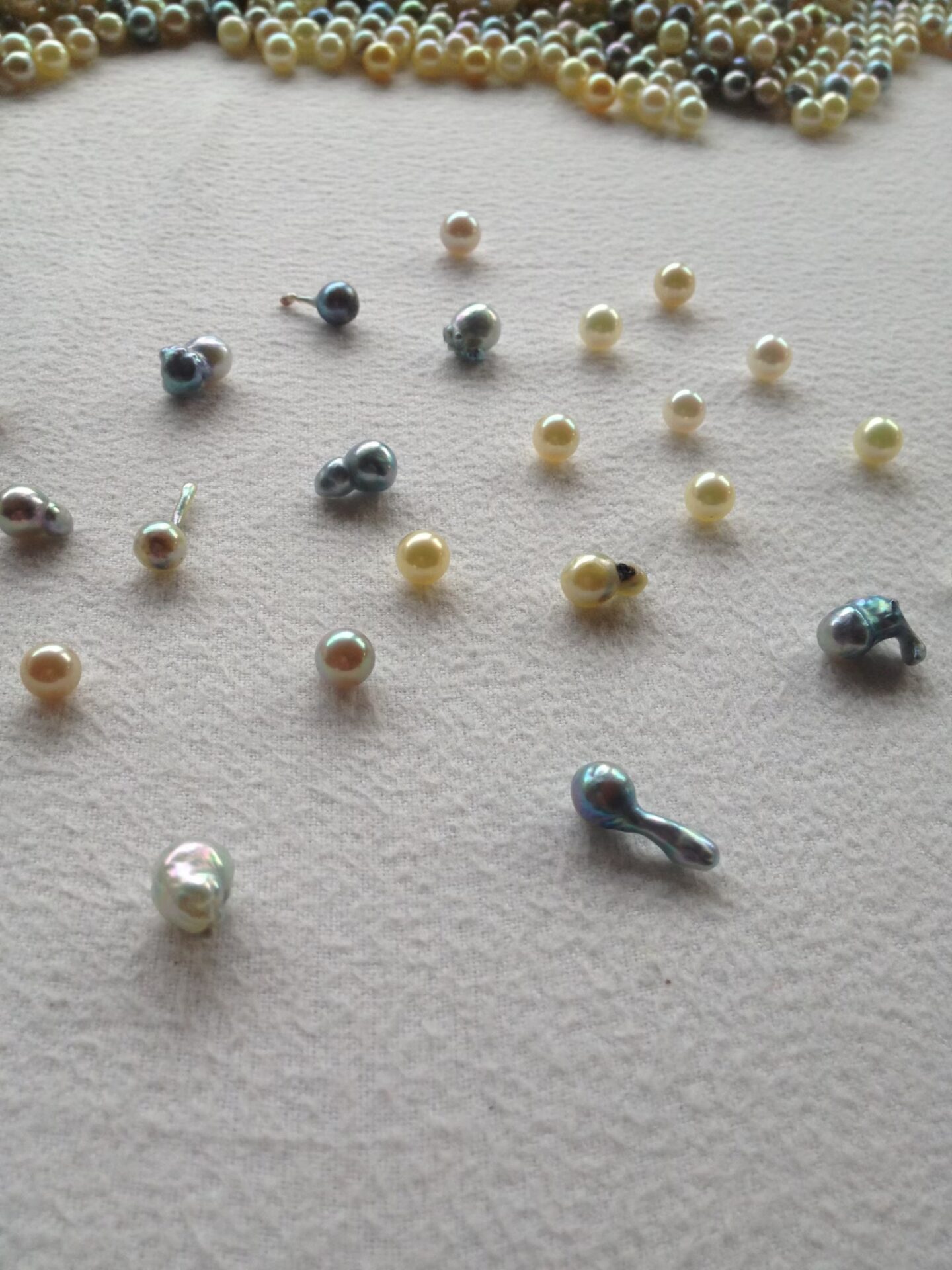

The next hardest challenge was sorting the third-grade pearls.

The sorting criteria for first-grade pearls are simple: round, high-luster pearls with no wounds or at most one tiny blemish. This was an easy rule to follow.

For second-grade pearls, we selected the group with the strongest luster from those excluded from the first-grade category, allowing up to two tiny wounds. These were still close to first-grade pearls, making them relatively easy to sort.

Third-grade pearls, however, are selected from pearls that had fallen out of the first and second grades. The criteria state that they must have strong luster, allow for medium-level blemishes or wounds, and can be slightly misshapen rather than perfectly round.

The rule that “medium-level blemishes or wounds are allowed” was vague, and since different supervisors had slightly different interpretations, it took me more than five years to master this level of sorting.

Once again, an important point was, “Don’t just look at the surface of the pearl. Be sure to assess the thickness of the nacre.” Even if a pearl appeared round with few blemishes on the surface, if it had thin nacre, it would be rated below third-grade. Conversely, a pearl with some blemishes but thick nacre would receive a higher evaluation.

The reason for this is that pearls with thick nacre are durable enough to withstand processing by jewelers who purchase them. Pearls with thin nacre may not be strong enough to handle the processing, meaning their surfaces could crack, making it impossible to remove blemishes. However, pearls with thick nacre are robust and can withstand such processes.

Approximately 90% of Akoya pearls on the market undergo blemish-removal treatment. While there are methods to treat pearls with thin nacre, this demonstrates the importance of nacre thickness.

Through this experience, I learned not only to judge pearls by their surface but also to evaluate the overall quality, including nacre thickness, and to sort each pearl accordingly.

During the pearl harvesting season, I sorted pearls at the pearl farms, and for the rest of the year, I worked on sorting at the head office in Kobe. Sorting pearls throughout the year was a core part of my job as a pearl merchant.

Through this process, I gradually grew to love pearls. In fact, I often found pearls I liked so much that I wanted to take them home and sleep with them. These pearls were often blue baroque pearls. Baroque pearls have particularly thick nacre, which gives them a deep luster and glow that I found captivating.

While perfectly round pearls are common, baroque pearls, each with their unique character, are one-of-a-kind treasures. Since baroque pearls are considered “imperfect” at pearl farms, I felt an attachment to them.

On the other hand, I had little interest in necklaces. Even when I saw a 10mm Hanadama necklace being sold in the company, my reaction was, “So what? You may be beautiful, but you’re empty-headed, aren’t you?” I wasn’t very impressed.

Round, white pearls were always popular, but blue baroques weren’t very well received at the time. Perhaps I was a little envious of the popular beauties like Hanadama pearls. Actually, I still feel that way to some extent.

However, while I liked loose baroque pearls, I wasn’t particularly drawn to baroque necklaces.

That said, my job at the pearl company was incredibly fulfilling, as I was surrounded by beautiful pearls every day.

I was also in charge of managing the company’s Instagram and Twitter accounts. I had asked for permission to run them when I first joined the company. Initially, the company was skeptical about using social media, but as our follower count grew, my boss came to support it. Early on, he would even scold me, saying, “Stop using Twitter during work hours.”

Despite that, I spent my off-hours cultivating relationships with new customers through Twitter and Instagram. I vividly remember my boss frequently making snide remarks like, “You seem to enjoy small-time business.”

Amid all this, my passion for pearls continued to deepen.

And then, one day in 2019, while I was browsing Instagram, I saw a pearl necklace made with colored threads for the first time, and I was blown away. I thought, “How cute!”

I immediately called the pearl company that made the necklace. I told the representative, “That pearl necklace is really cute! I’ll try making one too.” Looking back now, the person thanked me, but they might have been a bit taken aback by my enthusiasm.

I shared my excitement with my boss and colleagues at work, but their reactions were quite negative.

“Cute? All-knot has been around for ages. You didn’t know that?”

“We don’t need to do All-knot anymore. Back in the day, it was necessary because silk thread broke easily.”

“Nowadays, synthetic fiber threads don’t break that easily.”

“All-knot? It’s a hassle and not necessary.”

Despite this, I learned how to make it by watching YouTube videos.

I’d go home from work, and every night from 6 PM to midnight, I practiced. After about two weeks, I finally got the hang of it.

Around that time, a friendly customer from my retail work told me about Etsy.

The customer said, “You really love pearls. Why not try selling on Etsy?”

That’s when I decided to spread the word about All-knot necklaces through Etsy.

For a pearl merchant, All-knot isn’t anything special, but for someone like me who knew nothing about it, it seemed like a treasure. Ignorance can be a powerful thing.

Incidentally, my connection with this customer, who introduced me to Etsy, began when she called our company.

She had purchased a blue baroque pearl necklace from our company and was so impressed that she called to express her thanks.

During our conversations, I realized, “This person might love pearls even more than I do!” Her passion was overwhelming.

I invited her, saying, “Please come visit the company. We have so many pearls you’ll love!”

But she told me she had a physical disability and couldn’t make the long trip to our company from where she lived.

A collection from a customer in Wakayama.

At that time, I had just gotten my motorcycle license, so I said, “I’ll bring the pearls to you.”

So, on my day off, I rode my motorcycle from Kobe to Wakayama Prefecture to meet her.

Since I was a new rider, I was too scared to use the highway, so I took the regular roads.

It took about seven hours, riding in the cold of early November, with me shivering and worrying about running out of gas.

I thought, “Wakayama? It’s not that far on a motorcycle,” and left in the evening.

But once I passed Osaka, it was all mountain roads. The path was pitch black.

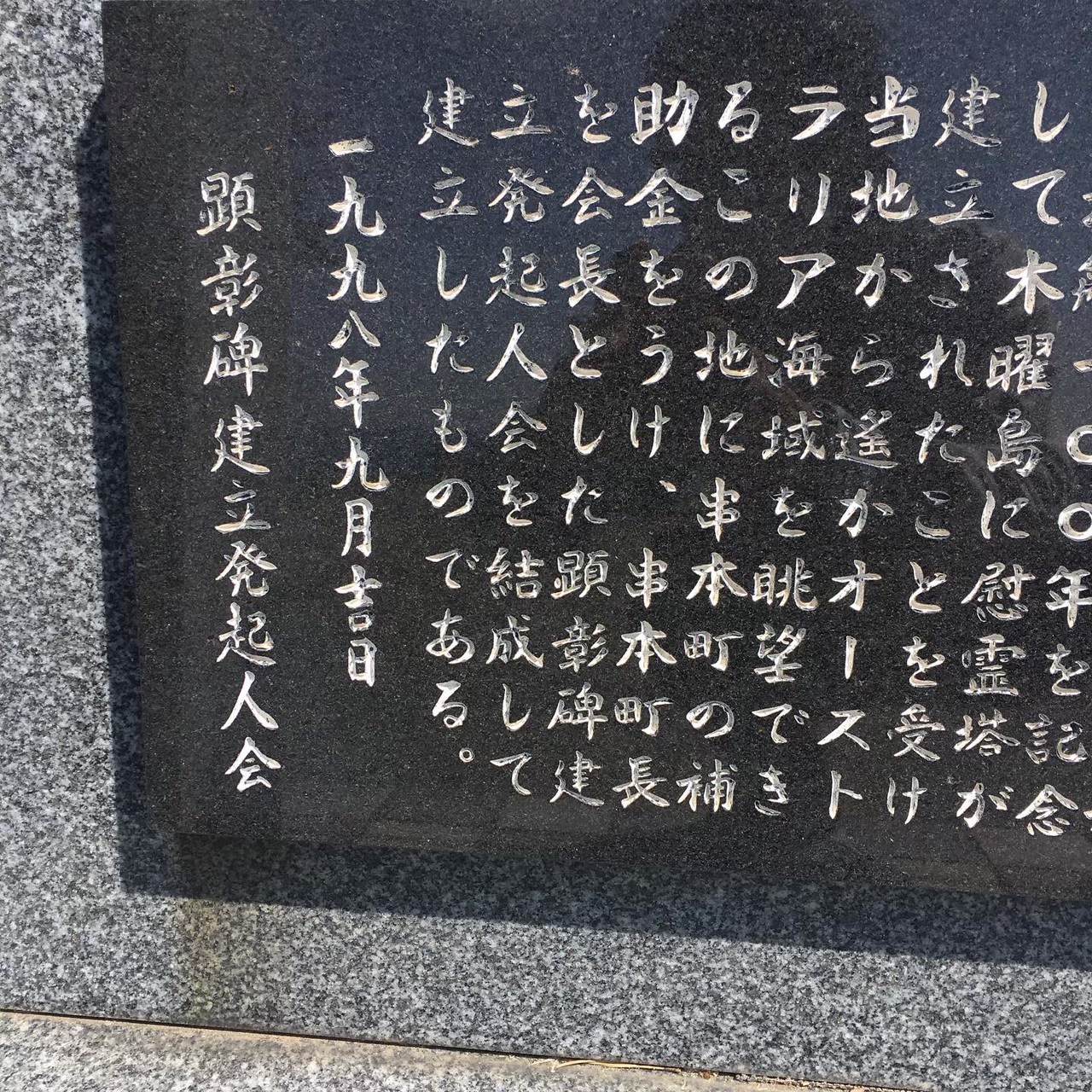

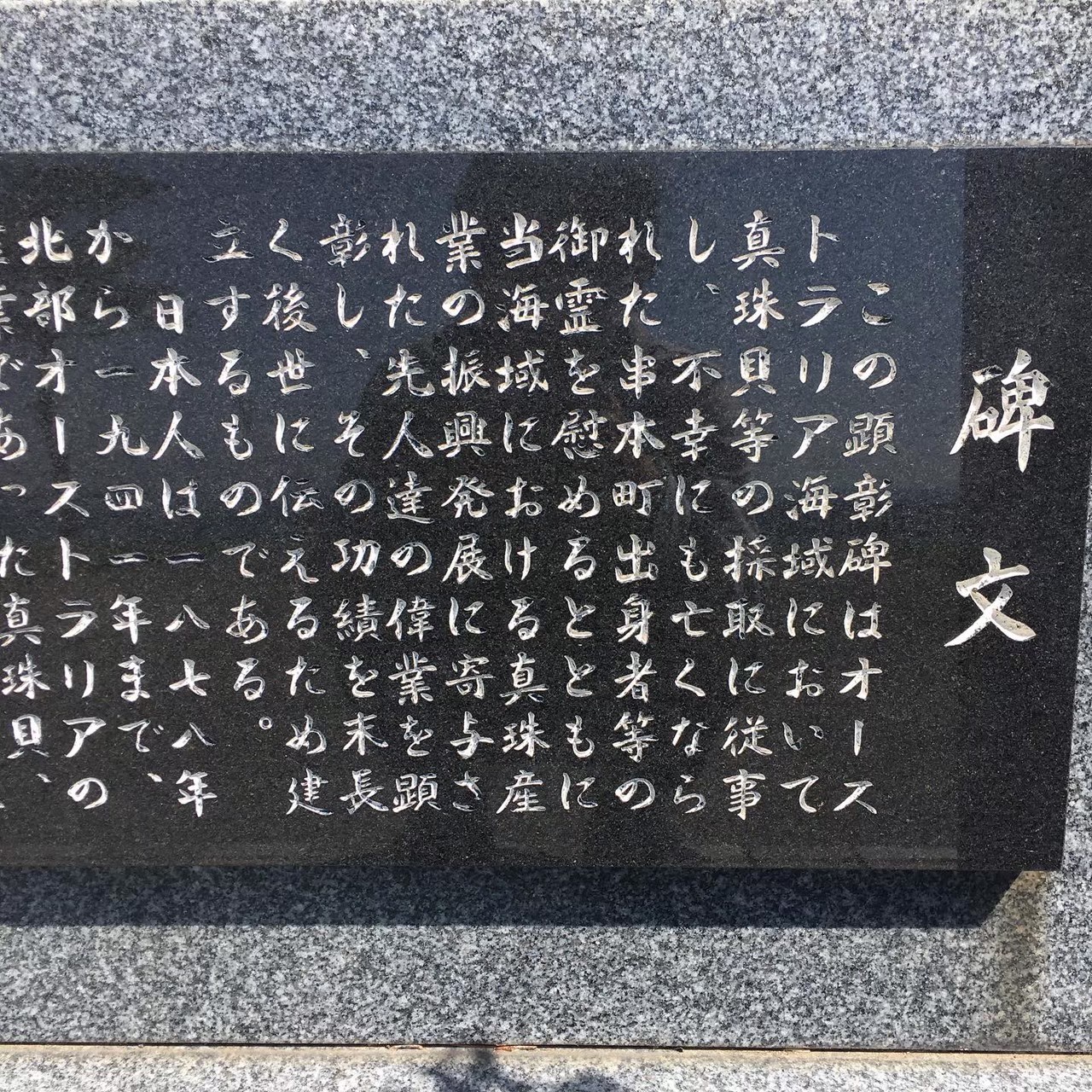

The southernmost point of Honshu is located in the southern part of Wakayama Prefecture. There is a monument there. Below is a translation of this inscription:

This monument was erected to console the souls of those from Kushimoto who unfortunately passed away while harvesting pearl oysters and other shellfish in Australian waters, as well as to commemorate the great achievements of our predecessors who contributed to the development of the pearl industry in this area and to pass on their achievements to future generations. From 1878 to 1941, Japanese people were employed in the harvesting of pearl oysters, oyster shells, and sea cucumbers, which was an industry in northern Australia, and worked together with the islanders to discover fishing grounds, improve fishing methods, and make this fishing a core industry, thereby contributing to the development of the region. Following the construction of a memorial tower on Thursday Island to commemorate 100 years of Japanese immigrants to Australia, this monument was erected with a subsidy from Kushimoto Town, on this site, which overlooks the distant Australian waters, by a committee of promoters for the construction of the monument, chaired by the mayor of Kushimoto Town. September 1998: Monument erection promoters meeting

The monument is facing in the direction that Australia is said to be far away. I don’t know why, but it brings tears to my eyes to think about these people over 100 years ago, even though I have no idea how they actually engaged in that fishery.

※By the way, the text and images of these annotations are not included in the video at all.

I found myself clinging to the tail lights of a car in front of me as I rode.

At one point, the car turned into some kind of facility, so I followed it in.

I asked the driver, “Are you going to Wakayama from here? If so, may I follow behind you? There’s about 100 kilometers of roads like this ahead, and I’m a new rider. I’m scared to ride these dark mountain roads alone.”

He replied, “Sorry, my family and I came here to enjoy this star-gazing observatory. Unfortunately, I won’t be able to help, but I wish you a safe journey to Wakayama.”

So, I continued alone toward Kushimoto in Wakayama Prefecture.

As usual, I hadn’t thought much about my attire, so I was in regular clothes.

The weather in early November, transitioning from autumn to winter, was freezing at night.

My legs were shaking as if they were cramping.

There were no gas stations, and the only sign of life was the occasional small village every so often along the 100-kilometer stretch of road.

There were no traffic lights, and barely any cars were on the road.

I started to feel real fear: If I ran out of gas in the middle of these mountains, it would be the end.

I stopped at a small restaurant in a tiny town along the way to have a meal.

My hands were shaking so much from the cold that I couldn’t hold my chopsticks properly, and the owner asked, “Are you okay?”

I asked the owner, “Is there a gas station nearby?”

He said, “If you ride for 10 more minutes, there’s one. But it closes at 8 PM.”

I checked the time: 7:45 PM.

I quickly finished my meal and rushed to the gas station, but it had already closed.

In the end, I continued riding for another three hours and finally arrived at my destination.

Usually, when I think, “It’s about time to refuel,” I can only fill up about 8 liters of gas.

But when I refueled in Wakayama, I put in 12.80 liters.

The tank capacity is 13 liters, so I was cutting it very close.

When I finally got to the inn in Kushimoto and soaked in the bath, I let out a huge sigh of relief, one of the biggest of my life.

“Aaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhh!!!!”

It was one of the top moments of happiness, relief, and a feeling of coming back from the brink of hell to heaven in my life.

Yes, Japan is peaceful.

This has been a long story, but I wanted to share a bit of the background behind my connection to All-knot.

Is this video helpful for learning how to master All-knot?

If you have any questions or doubts, please feel free to leave a comment.

**************************************************

The above is the article I prepared for the subtitles of that video. In reprinting this article, I spent more time filming a new video as a supplement. However, I was especially moved to tears when translating the stone monument I found when I went to Wakayama. I went to Wakayama to meet people who love pearls, and not only did I learn about Etsy, but I also encountered traces of our ancestors who dedicated their lives to pearl oysters more than 100 years ago.

Anyway, this time too, I was just going to repost the subtitles of the video, but a lot of stuff was added to it. I can’t be a novelist.

Comment