Sixty Series is a collection of Akoya pearls harvested more than 60 years ago — pearls that embody forgotten dreams, silent resilience, and the beauty that deepens with time.

Sixty years ago, the world was a place of dynamic change led by young people. In the United States, the civil rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War shook society. In France, the May Revolution erupted. In Japan, the Anpo protests took place, while movements for Black liberation and environmental activism were taking root. It was a time when values shifted dramatically, and the music of the Beatles and Bob Dylan became symbols of counterculture.

The Akoya pearls harvested in that era — more than six decades ago — are what I call the Sixty Series.

These pearls had remained untouched and asleep for over 60 years. They were originally owned by Yasui Tōdō, the man who invented the pearl stain removal technique — a process now considered indispensable, applied to at least 90% of all pearls distributed in the world except for natural blue ones. Thanks to a connection I made a few years ago with Tōdō’s great-grandson, I was able to encounter these remarkable pearls.

Although I spent only ten years in the pearl industry, I knew of Tōdō’s contribution to stain removal. However, I knew little about his actual work or the history of Sukumo, his hometown, and its connection to pearl cultivation. The more I researched, the more fascinating stories I discovered — and I’ve written about many of them.

To summarize for those who don’t have time to read the full article:

In the history of Akoya pearls, round pearls were successfully cultivated in Sukumo, Kōchi Prefecture, even before Mikimoto. The dream of that place was lost to a catastrophic flood. The “Sixty Collection,” pearls over 60 years old inherited from the great-grandson of Tōdō — the inventor of the stain removal technique — have thick nacre from their long cultivation and still retain their beauty today. They may not be the most visually stunning pearls, but they carry within them history, human effort, and memories of a dream that vanished — making them profoundly romantic and meaningful.

The article also describes how it took several years for the pearls to return to me after being sent for stain removal — far longer than usual, even though they were already over 60 years old.

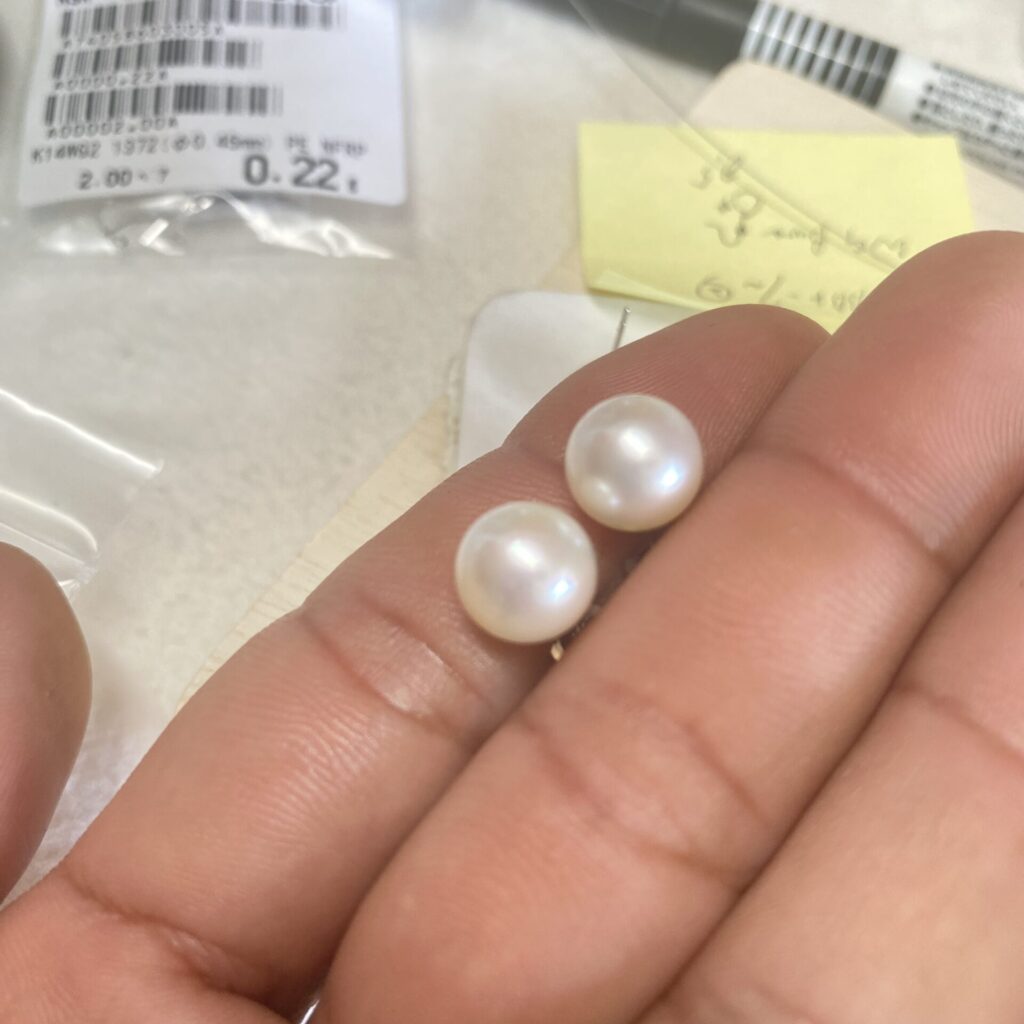

The largest pearls in this series are 9 mm, and the smallest are 5 mm.

I began by working with the 9 mm pearls, first selecting the finest ones for earrings, and then choosing others for bracelets. As I handled these pearls, I found myself thinking of Sukumo — a place that could have been the true holy land of pearls, had it not been for the great flood.

The sea of Sukumo is still rich and nurturing. Even today, some pearl farms bring young Akoya oysters there to grow before returning them to their local waters for cultivation. When I visited Sukumo regularly, elderly people in the industry would sometimes tell me, “If only that great flood hadn’t happened.”

Back then, I didn’t fully grasp what they meant — only that a once-thriving pearl farm had been destroyed. But after gathering more information while working with the Sixty Series, everything suddenly made sense.

Mikimoto was the first to succeed with semi-spherical pearls, but Sukumo had already achieved success with round pearls. The company in Sukumo was called Yodo Suisan Co., and Yasui Tōdō was a major investor and supporter. They even exhibited shell products and pearls at the San Francisco World’s Fair, receiving high praise and letters of appreciation. Yet all of it was wiped out by the flood.

One of the people involved in Sukumo’s round pearl success, Masayo Fujita, later achieved round pearl cultivation together with Kokichi Mikimoto. That is why Mikimoto is now credited with the “world’s first” round pearl — a result perhaps of superior marketing, branding, and sales power.

Today, many in the pearl industry say, “It’s fine to let Mikimoto be the first. No one cares about Sukumo anymore.”

I’m not particularly interested in arguing about who was truly first. But to me, Sukumo has become a “lost holy land of pearls.”

The town is now quiet and somewhat faded. In recent years, a few people who trained in Tokyo have opened stylish restaurants, but overall it remains a sleepy place. And that’s why the old fishermen always said, “If only the flood hadn’t happened.”

This kind of gap between fact and recognition happens all the time. Kobe is known as a “pearl city,” yet most citizens don’t know it. There are about 200 pearl businesses here, but most are wholesalers, so you’d never guess it from the street. Similarly, Ehime produces the most pearls in Japan, followed by Kyushu (Oita and Nagasaki), and then Mie — yet most people still associate pearls only with Mie and Mikimoto.

It’s like a household where the wife does everything to support the family, but the husband — who does nothing — gets all the praise. Reality and recognition often don’t match. Some people work tirelessly but remain unacknowledged, while others who do less are celebrated.

The Sixty Series pearls from Sukumo — a “phantom pearl sanctuary” — evoke those thoughts for me.

“Sounds like an unlucky pearl,” someone might say. But not necessarily.

After more than 60 years, these pearls are now shining again as finished jewelry. I believe many people are in situations where they haven’t yet been rewarded for their efforts. Some should walk away, but others need to persist. Either way, we all hope to shine someday.

Even if a pearl is slightly flawed or cloudy, it can still be beautiful — just as the depth and character we gain with age are beautiful too. That’s the feeling behind the names I give each piece in this series.

One of them is a bracelet called “Jiku” — meaning “time and space.”

A bracelet made with 9 mm pearls that have crossed six decades to shine in the present. Its soft luster carries weight and depth. Perhaps the unique aura it radiates comes from knowing its history. It’s perfect for those who prefer understated jewelry — a gentle streetlight guiding you through the night, or the soft, persistent glow of the moon that never tries to outshine the sun.

And then there are the earrings:

Each name is inspired by Sukumo — the lost pearl sanctuary. Some of them are even common Japanese given names today.

I hope that people who wear these pieces will not only appreciate their beauty but also understand their historical background. And I hope that, like these pearls, which have gone through many twists and turns yet continue to shine, they too will keep shining — no matter what their past holds.

After all, to shine is to be happy. And all of us, in our own way, are seeking happiness.

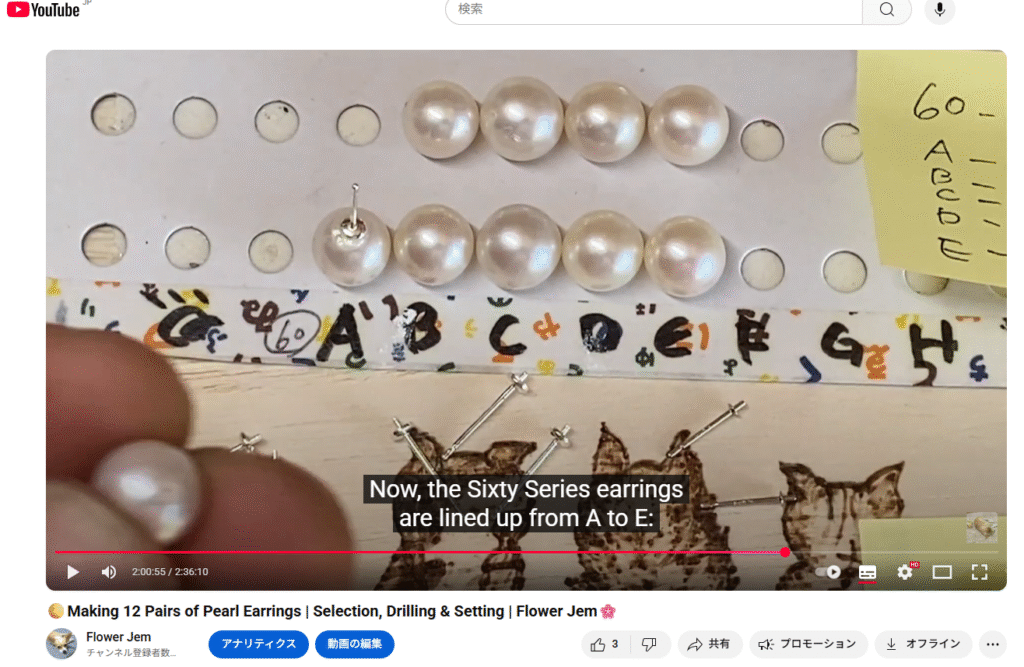

As an additional note: The making process of these 9 mm earrings from the Sixty Series is featured in the video below. Starting at 2:00:50 (2 hours and 50 seconds), you can see all the pearl earrings lined up together, allowing you to compare their quality and atmosphere. I hope you’ll enjoy watching it.

A to E correspond to each individual piece as follows:

A – Nukumori (Warmth)

B – Tsuioku (Reminiscence)

C – Towa (Eternity)

D – Haruka (Distant)

E – Kanata (Beyond)

See you again.

Pearl bless you.

Comment