I was in my third year working for a pearl company when I bought my first Akoya blue baroque pearl through the company.

After seeing it every day, I realized I had truly fallen in love with pearls.

In my case, I experienced firsthand who was cultivating these pearls, where, and how—

so naturally, I became emotionally attached.

Pearls are harvested every year around New Year’s,

but each year has its own characteristics.

When it comes to blue pearls, one year might bring soft, pale blues;

another might produce pearls that appear blue not from within but from surface blemishes.

Some years bring a sky-blue tone—deep but transparent.

Others lean toward greenish-blues. It really varies.

I also spent two years listening to the farm manager talk about the Akoya oysters he had been preparing for two years.

So when those oysters finally produced pearls,

in a way, I had been following their story for four years.

There are also the technicians who insert nuclei into the Akoya oysters.

From April to December, they insert about 800 nuclei a day.

They each come from different personal backgrounds, and their skills vary widely.

Some are doing well. Others have had years of poor results.

But no matter the weather—hot or cold—they face the Akoya oysters and work earnestly.

All of these memories, all of this experience, have made me fall even deeper under the spell of pearls.

…And with that, I seem to have already veered off-topic.

Let’s get back to the value of baroque pearls.

Most of my friends, acquaintances, and family members have no interest in pearls.

When they saw my baroque pearl for the first time, they asked:

“It’s pretty, but isn’t it worthless because it’s not round?”

“Are pearls that aren’t round even a thing?”

When I used to sell pearls at a physical store,

I once had a customer who loved baroque pearls say to me:

“I wish pearl farms would grow more baroque pearls.”

So I’d like to respond to all of those thoughts at once.

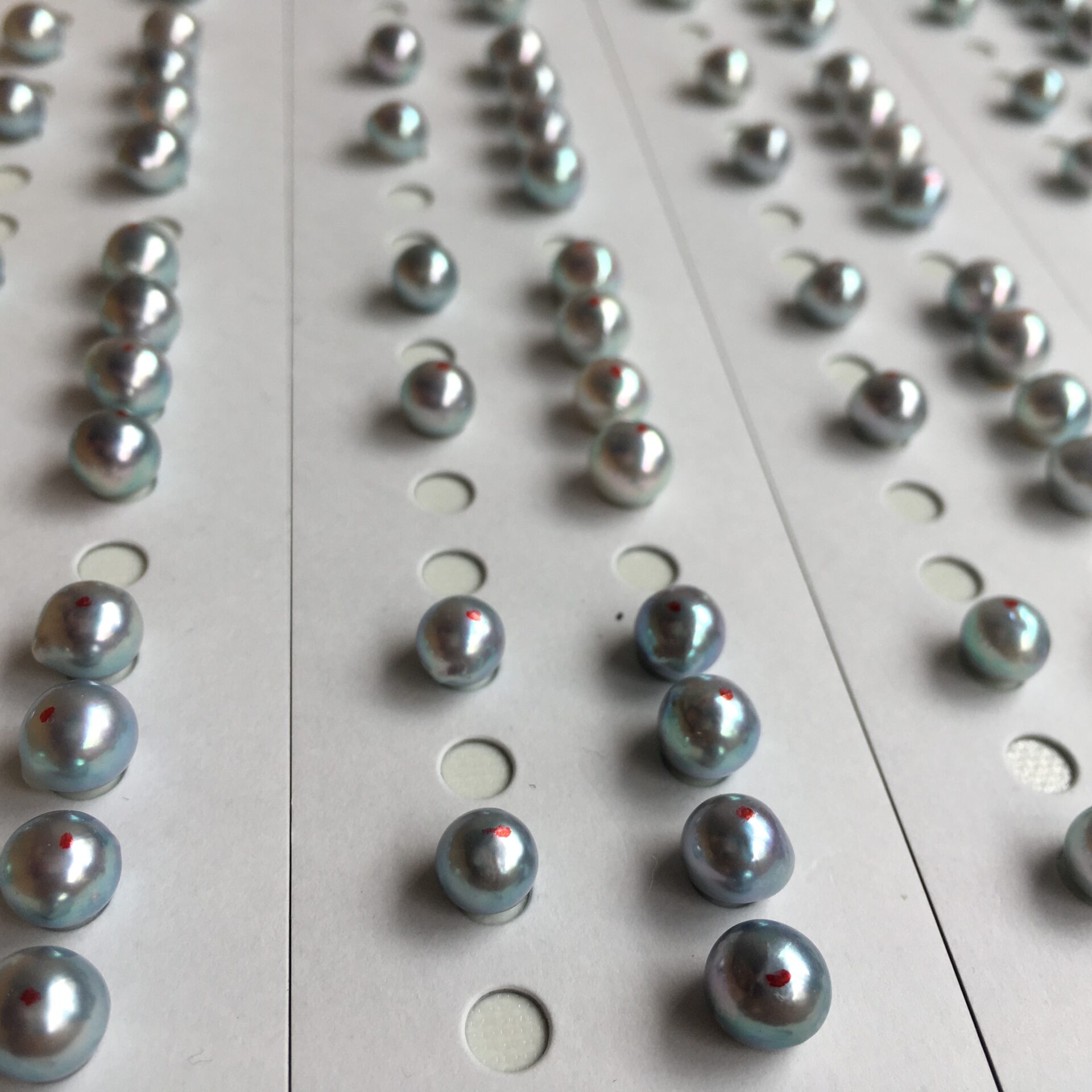

First of all, nearly all Akoya pearl farms aim to produce:

“Round, blemish-free pearls with strong luster, thick nacre, and a whitish tone.”

That’s because those are the pearls that fetch the highest prices

at the exclusive wholesale auctions held immediately after harvest.

In comparison, baroque pearls are consistently valued lower at these auctions.

For example, if a first-grade round pearl sells for $66 per momme (3.75g),

a first-grade baroque pearl might go for about $40.

And let me clarify: that $40 would be for a top-tier baroque pearl.

An average first-grade baroque might drop as low as $15.

No matter how beautiful it is, just being “baroque” lowers its price.

Most pearl dealers who purchase harvested pearls do so to process and sell them

as formal, standard pearl necklaces.

So, baroque-shaped pearls aren’t really needed in large quantities.

You might think,

“Well then, why don’t they just produce round pearls?”

If a pearl farm manager heard that, he’d probably hold his head in his hands.

Because that’s what he thinks about, 24 hours a day.

“How can I increase the percentage of round pearls, even by 1%?”

Even if the spot where the nucleus is inserted is off by just 0.1mm, the pearl can turn out baroque.

If the farm planned to hang the oysters in shallow waters to match rising sea temperatures—

but then the sea warmed faster than expected—

the oysters could become stressed and start producing baroque pearls.

During extremely hot summers, some Akoya oysters die due to heat stress.

But others, thriving in the heat, produce thick nacre in large quantities—

and that excess can also result in baroque shapes.

Producing round pearls is incredibly difficult.

There’s a rumor about one pearl farm with such high skill that they produce almost only round pearls.

For six years, no one believed the story.

But when our farm manager visited them, he told me:

“I was speechless. It’s true.”

That’s an exceptional case.

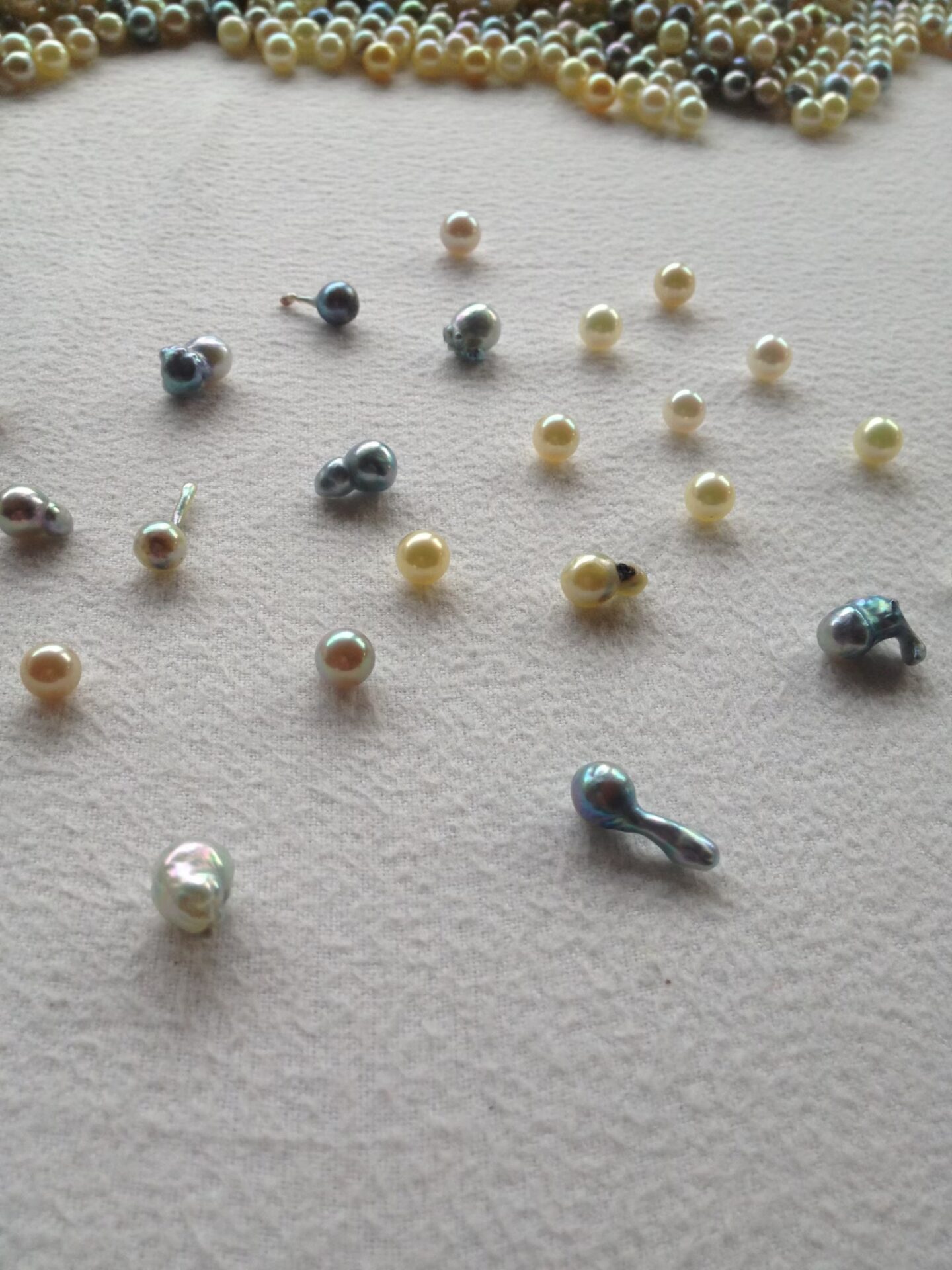

Generally speaking, about 40% of pearls end up baroque.

The percentage changes every year, but that’s a rough average.

So then, from the perspective of pearl farms,

baroque pearls are essentially considered failed products.

Until fairly recently, some farms would even throw blue baroque Akoya pearls straight back into the sea.

But over the past ten years or so, those previously undervalued blue baroque pearls

have started to gain recognition and find their place.

In Japan, I think it was about 20 years ago that we began to see changes in the vegetables sold in supermarkets.

Typically, cucumbers and tomatoes on the shelves were all very uniform in shape.

But in some stores, you started to see more irregular, crooked shapes—

cucumbers that curved or tomatoes with lumpy sides.

They may look odd, but they taste just as good.

My father is about 77 now, but when he was around 40,

he started growing vegetables as a hobby.

Back then, my two brothers and I were in elementary school,

and every Sunday, we were basically his unpaid farmhands.

In summer, we had to water the watermelon plants.

We’d carry buckets of water from a well located about 10 meters away—

a well that belonged to someone else (though we had their permission).

My dad wasn’t particularly skilled at growing watermelons.

He often gave them too much fertilizer, and they’d burst open.

But the ones that burst?

They were incredibly sweet and delicious.

Each summer, he harvested about 20 to 50 watermelons.

There were five people in our family.

We didn’t need 20 watermelons per summer.

The small fridge at our house was always stuffed with a giant watermelon,

as if it had taken up permanent residence.

He also grew cucumbers.

Some of them had grown in full spirals—probably due to the fertilizer.

His tomatoes were oddly shaped, like they’d been squashed by hand.

The eggplants were twisted and swollen,

like oversized gourds—nothing like what you’d see in a typical supermarket.

Maybe it’s because of those experiences

that I’ve grown to love baroque pearls so much.

…But let me be honest:

there’s actually no real connection between those experiences and my love for baroque pearls.

What I really want to say is this:

The shape of a vegetable has nothing to do with how good it tastes.

In fact, the misshapen ones are often better ripened and sweeter.

You probably already know where I’m going with this, right?

It’s the same with pearls.

Even if the shape is irregular—

it’s precisely because of that irregularity that the nacre grows thicker and becomes more alluring.

No matter how perfectly round a pearl is,

if the nacre is thin, it ends up looking like a plastic bead—flat and shallow.

What truly defines the beauty of a pearl is

the rich, luminous glow that comes from thick layers of nacre.

A youthful, cheerful smile can be delightful, of course.

But a quiet smile from someone who has endured decades of hardship—

that kind of expression can wordlessly touch the hearts of those who see it.

If a young person blinks slowly,

you might just think,

“Oh, are they sleepy?”

But if an elderly person blinks slowly,

it somehow feels poetic.

It makes you wonder,

“What kind of memories are passing through their mind from the past seventy years?”

That said, older people today—those over seventy—

often seem far younger than the elderly we knew in the past.

Back then, it was common to see elderly women hunched over,

staring down at the ground as they walked.

My late grandmother used to walk like that—

head down like a miniature excavator.

…And I’m off track again.

When it comes to pearls,

nacre is depth.

It’s like when a convenience store clerk says “thank you” in a mechanical tone—

and when a mother receives a bouquet of flowers from her rebellious, lazy teenage son

and softly says,

“Thank you.”

That’s the kind of difference that exists

between a thin-nacred pearl and a thick-nacred one.

So, to answer the question:

“Do baroque pearls have value?”

Yes. Absolutely.

Of course, there are times when appearance is important.

In formal settings, round pearls are preferred.

They fit the occasion, they look refined, and they meet expectations.

But when you want to wear something truly beautiful—

its shape doesn’t matter.

A round pearl with a thin layer of nacre and dull luster

may be outshined by a baroque pearl with deep, radiant glow from its thick nacre.

That kind of beauty—

not surface-level, but something that comes from within—

is what truly moves people.

You might say,

“I don’t care whether my jacket is made of real cowhide.

If it’s from a famous brand, I’m fine with synthetic leather.”

That’s a valid perspective, too.

But if you shift your focus to whether it’s a truly excellent leather product,

then brand alone doesn’t define its value.

There are outstanding leather goods from famous brands,

and also remarkable ones from unknown makers.

The difference with baroque pearls is that

even if they are inherently beautiful, they’re still priced lower than round pearls.

Since pearls are generally expensive to begin with,

baroque pearls offer a relatively affordable option within that category.

If you buy a necklace from Mikimoto, the price is staggering.

But if you find a pearl of the same quality from a lesser-known brand,

you might get it for less than half the price.

Mikimoto carries some baroque pearls, too—

but even those are high-end items.

If you’re not fixated on brand,

and instead focus on the thickness of the nacre and the quality of the luster,

you can find genuinely beautiful pearls at more approachable prices.

…So, I’ve written all this,

but now I’m starting to wonder if I actually stayed on topic.

But I think that, whether it’s pearls or anything else,

there are three kinds of value:

- Market value

- Personal taste or preference

- Intrinsic value

Baroque pearls have low market value.

Whether someone likes baroque or not depends on personal preference.

And when it comes to intrinsic value,

it doesn’t matter whether a pearl is round or baroque—

shape has nothing to do with it.

Whenever I think more deeply about these three types of value,

I start to feel like there’s some kind of hint about life hidden in there.

Your market value.

The way others evaluate you.

And your truest self—who you really are.

…I don’t know.

My brain feels like it’s about to freeze,

so I think I’ll stop here.

So in the end, this article about baroque pearls

turned into a reflection on why I personally love them so much.

I don’t expect anyone to fall in love with baroque pearls just by reading this.

But if it made you think,

“Oh, I guess baroque pearls can be beautiful too,”

that alone would make me happy.

And if, at the supermarket, you happen to see a funny-shaped tomato or a crooked eggplant—

please say to it,

“So you may look a little twisted, but I hear that just means you’re fully ripe, huh?”

…and take it home with you.

That’s all for this article.

Today is April 10, 2025.

Here in Japan, it’s Tariff Festival Season.

Various commentators are voicing their opinions every day.

Their job is to get attention, after all,

so sometimes it feels like they change their views as easily as a chameleon changes its color.

Even among top analysts and scholars, opinions and predictions vary wildly.

Honestly, someone like me can’t hope to understand any of it.

But I imagine that whoever is at the center of all this noise—

he probably has his own vision

and is flipping the carpet over for reasons he believes in.

That said, I’m not the Prime Minister of Japan,

nor do I have any influence whatsoever,

so my only role is to observe from the sidelines.

My modest index investments are getting tossed around too, just like everyone else’s.

With pearls, I’d love to buy more when the market dips.

But with investing, I prefer to buy a fixed amount regularly, no matter what the market does.

And apparently, the World Expo is happening soon.

The media is buzzing,

but no one around me is talking about it.

What I’m more concerned about is the traffic restrictions on the expressway tomorrow night

as I head back from Osaka to Kobe.

It seems that, in preparation for the Expo, some areas in Osaka will have road closures.

I just hope there aren’t too many traffic jams—

and that I can get back to Kobe quickly.

Comment