It’s already the halfway mark of 2025.

On weekdays, I live in the southern part of Osaka, near Kansai International Airport where the Expo is currently being held.

Recently, the weather has been fluctuating—some nights exceed 25°C, while others are chilly and rainy.

Tonight, it’s 25°C, but the dry air makes it a comfortable evening.

I usually dedicate my weekends to pearl work, but last Saturday, I rode my motorcycle from Kobe to Kyoto for an oil change.

On Sunday, I went on a touring trip with a business contact, also by bike.

As a result, most of my usual pearl time was lost that weekend.

Normally, I would have given up and returned to Osaka as is,

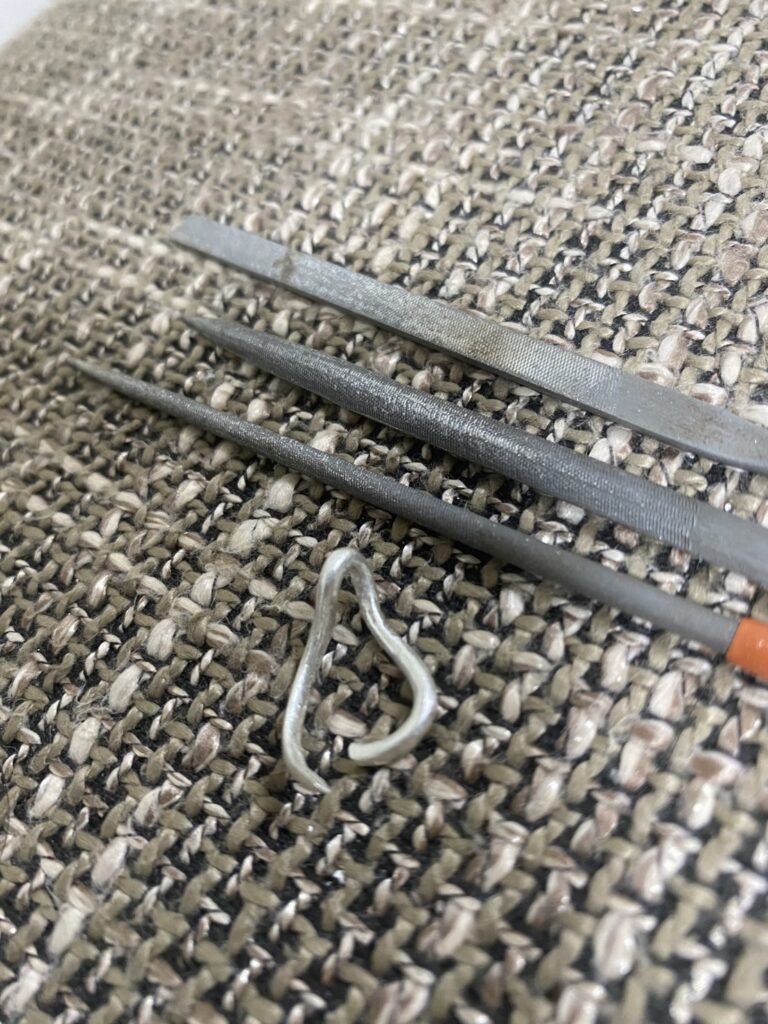

but this time I brought a half-finished silver pendant with me and did a little metalwork.

It’s clear now that weekends alone are not enough.

So—though it’s a bit late—I’m now plotting to equip my Osaka apartment with metalwork tools so I can keep creating even on weekdays.

Now that it’s June, I thought I’d share a little about pearl farming for a change.

At Akoya pearl farms, the oysters are carefully raised to produce pearls.

In simple terms, the farms manage the health and condition of the oysters so they’re ready for nucleus insertion.

One key requirement for an oyster to be suitable for this process is that it must not be carrying eggs.

By the way, Akoya oysters are hermaphroditic.

If an oyster is carrying eggs when the nucleus is inserted, the resulting pearl is highly likely to have blemishes.

Even if the pearl is perfectly round and has excellent luster, blemishes lower its auction price.

Nucleus insertion is performed from April to December each year.

An average technician will insert a nucleus into 800 oysters a day.

Most oysters receive just one nucleus, though about 20% may receive two.

This may be due to slow oyster growth or simply a shortage of available oysters.

Larger oysters can accept nuclei that may grow into 8mm pearls.

But inserting such large nuclei into small oysters often leads to rejection or even death.

Pearl trading is fundamentally a business of weight.

The larger the pearls, the more valuable they are.

If all your oysters are small and slow-growing,

you can’t produce large pearls and thus can’t increase total weight or revenue.

Let’s run the numbers:

An 8mm pearl weighs about 0.2 momme.

(1 momme = 3.75 grams, so 0.2 × 3.75g = 0.75g per pearl.)

Assuming 60% survival:

800 oysters × 0.6 × 0.75g = 360g per day of harvested 8mm pearls.

A 6mm pearl weighs about 0.1 momme = 0.375g.

800 × 0.6 × 0.375g = 180g per day of harvested 6mm pearls.

In short: half the weight, half the revenue—for the same amount of labor.

If the average market price is $40 per momme:

- 8mm: 360g = 96 momme → $3,840/day

- 6mm: 180g = 48 momme → $1,920/day

Over 180 working days, that becomes:

- 8mm: $3,840 × 180 = $691,200/year

- 6mm: half that

That’s why pearl producers prefer oysters capable of growing larger pearls.

But size alone isn’t enough—technical skill is essential.

Without it, only one pearl per oyster can be produced.

For example, at a farm I know well, located in a colder sea where oysters grow slowly,

there are now few technicians left who can insert two nuclei per oyster due to veteran retirements.

They still produce high-quality 6mm pearls, even good enough to sell to a famous brand—let’s call it “M.”

But their annual yield is low, and so is their revenue.

Now, about oysters and their eggs.

Healthy oysters tend to produce eggs.

But when their condition worsens, they release them.

Pearl farmers use this trait to time the nucleus insertion for when oysters are egg-free.

Preparations begin the previous autumn.

Egg-carrying oysters are packed tightly in small black baskets, like a rush-hour train.

The stress causes them to release their eggs.

Then, as winter arrives, seawater cools and the oysters go dormant.

They stay egg-free through spring.

Similarly, egg-free oysters are kept in slightly suppressive conditions so they won’t produce eggs.

These two groups are used for nucleus insertion between April and early June.

Oysters managed this way are called “yokusei” (抑制)—suppressed oysters.

They are mature, about two years old, and prepared the year before.

Now, let’s talk about the oysters used from June onward.

For example, oysters used in June 2025 would have been born around February 2023.

They grow for two years before being ready.

But unlike suppressed oysters, they aren’t managed to be egg-free.

As seawater warms past 20°C in May, they begin producing eggs.

That’s why egg removal is necessary for oysters used in June.

There are several methods:

- Shallow Hanging:

Move oysters from 3m depth to about 1.5m where the water is warmer.

Oysters tend to release eggs in water temperatures they find “comfortable.” - Ozone Bath:

Place oysters in a warm, ozone-treated bath.

When combined with shallow hanging, most oysters release their eggs. - Sunbathing:

On sunny days, bring oysters onto the raft.

Exposure to sunlight can also help them release eggs.

June is a tricky time.

Not too cold, not too hot—so the egg-removal methods must be handled with care.

Some oysters release their eggs immediately, while others require multiple sessions.

Opinions differ on whether completely egg-free or slightly egg-retaining oysters are better for pearl quality.

Some say completely egg-free means the oyster is too weak,

and inserting a nucleus will only stress it further.

Others insist even a trace of eggs can lead to blemishes.

The key is not just whether eggs remain,

but whether the oyster’s health is trending upward or downward.

Even an egg-free oyster that is weakening may not produce good pearls.

The ideal condition is: no eggs, and improving health.

To remove eggs, oysters must first be stressed.

But overdo it, and they may not survive the “surgery” of nucleus insertion.

Some say: don’t completely exhaust them—leave a little vitality.

That way, they’ll regain energy over the next two weeks before insertion.

It’s like scolding a child:

Be strict, but leave them an emotional escape route.

If you do, they’ll bounce back and play energetically again.

(Not that I have any kids—so take this with a grain of salt.)

In July and beyond, the oysters release eggs naturally because it’s hot.

That part gets easier.

But summer also brings new issues—barnacles and other organisms cling to the oysters,

stealing plankton and energy.

In October, the farms begin winter prep:

- Egg-carrying oysters are made to release their eggs before winter dormancy.

- Egg-free oysters are kept calm to stay dormant.

These are the oysters used the following spring.

During the winter, oysters go dormant.

They rarely produce new eggs.

So, that’s my brief explanation of oysters, their eggs, and the timing of nucleus insertion.

I know it’s not easy to understand.

Even I didn’t fully grasp it until after five years.

Most farm workers don’t know the yearly cycle.

Only the farm manager and maybe one or two others understand when to use which oysters.

They’re handling millions of oysters every day.

It’s too much for everyone to track.

Managers carry long-term plans in their heads, thinking years ahead.

If you love gardening, maybe you understand.

You plant bulbs long before the flowers bloom.

Likewise, pearl farming requires planning far in advance.

Want rice? Prepare the cooker.

Going out? Dress up first.

Almost everything takes preparation.

Pearl making is no different.

Knowing this background might help you see your pearls in a new, deeper light.

Comment